[SUNDAY WITH AJAHN BRAHMAVAMSO 23 January 2005]

By Wong Kim Hoh

If you look at the fine print or the warranty on your birth contract, it will read: 'You can die in a tsunami, an earthquake, from cancer and all sorts of things.'

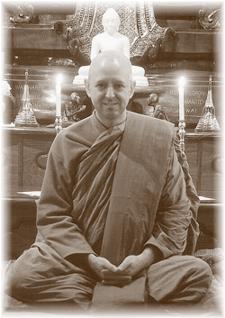

Singapore - Ajahn Brahmavamso is in the lift at the Singapore Buddhist Lodge just off River Valley Road. 'Press the N button, please,' the 53-year-old says with a very British accent. 'It'll take you to Nirvana.'

The occupants of the lift laugh. And Ajahn Brahm, as he is better known, breaks into a beatific smile.

The Caucasian clad in the seasoned saffron robes of a Buddhist monk was born Peter Betts in London in 1951. His late father worked in Britain's merchant navy and his mother was a secretary. He has an elder brother.

This Cambridge University alumnus has a master's in theoretical physics. He dug Jimi Hendrix and, as a child, harboured grand ambitions of becoming a train driver.

At 23, however, he was ordained a Buddhist monk and spent nine years in a forest monastery in north-eastern Thailand studying under Ajahn Chah, a renowned Thai meditation master.

As to what led him to the path less trodden, he recalls: 'In secondary school, I won a book prize for maths. My teacher told me to go to Foyles bookshop in London and pick a maths book.

'But I wasn't going to waste my first prize on a boring maths book, so I got one on all the major religions instead.'

Throughout this interview in the audio-visual room of the Singapore Buddhist Lodge, he sits legs crossed in the lotus position.

He adds: 'I wanted to choose a religion, but also wanted to be rational about it. I thought I should find out what each one teaches and then make my choice. Buddhism stood out. From that time on, I started calling myself a Buddhist.'

He was 16 then and led the life of a normal British teenager.

'I had girlfriends, drank alcohol, had sex and was very much into Jimi Hendrix.'

But at 23, after a couple of failed relationships, he decided to become a novice monk in Thailand.

'It was a beautiful time. I had a stable career and no obligations. If I wanted to become a monk for a short time to give my life some spiritual foundation, I thought this was the time to do it.'

Giving up drink and sex was not difficult, he says.

'It was good. You have a fair amount of experience in that area, so you know what you have given up.'

Life in the Thai forest monastery was very austere. 'The food was disgusting. You ate insects, ants, lizards and anything that crawled.'

However, he stayed because Ajahn Chah, his teacher, was very inspiring. The latter has since died.

'At Cambridge, I'd met rich people, people who have won Nobel Prizes, but this monk was by far the happiest and wisest person I'd seen. You just wanted to stay with him.'

And stay with him Ajahn Brahm did - for nine years.

In the early 1980s, he was invited to start a Buddhist monastery just outside Perth, Australia. He is now its abbot, and in October last year, was awarded the John Curtin Medal by Curtin University of Technology, for building a strong Buddhist community in Australia.

His proudest achievement took place on a Sunday two or three years ago in an Anglican cathedral in Perth.

'For the first time in the history of Christianity, a Buddhist monk gave a sermon and performed the Eucharist in a church on a Sunday, and that was me.'

Ajahn Brahm had become firm friends with the dean of the cathedral who invited him to talk. When word of that leaked, the dean received death threats. Countless letters debating the issue were printed in newspapers.

'In the end, it happened. People packed the hall and crowded around the windows. Half of them were Buddhist, half of them Christian, but no one knew who was what.'

He spoke on 'harmony and peace and love at the heart of all religions'.

'After giving that speech, we put our arms around each other and walked down the hall. The audience gave us a standing ovation for a long time,' he says, visibly moved by the recollection.

The abbot derives a lot of pleasure from talking about Buddhism to schoolchildren and prison inmates in Australia.

'It is perhaps a strange thing but in prison, people are honest. They'd tell me if they thought what I was saying is bulls***.'

One, he recalls, even taught him a lesson on the law of karma.

'This man's been in and out of jail for petty crimes. He said he never robbed people, only houses, because he said houses don't feel pain.'

One day the prisoner told Ajahn Brahm he was put in jail for something he didn't do.

'I told him I'd help him, but he smiled and said: 'But there have been many crimes I have committed for which I've not been caught. So this is fair.' '

Is it fair then that the tsunami happened and so many lives were lost? He relates an incident involving his teacher.

'A soldier came to Ajahn Chah and complained that he had been shot. My master asked: 'What do you mean? That's what happens to soldiers. You shoot people and people shoot you. It's part of the contract.' '

And that, he says, is the lot of humanity. 'If you look at the fine print or the warranty on your birth contract, it will read: 'You can die in a tsunami, an earthquake, from cancer and all sorts of things.'

'The strange thing is, most of us don't expect these things to happen to us. When we have accidents, we ask: 'Why me?' But these are the rules of life.'

Life, he says, is 'like a flower. It blooms for a few days before the petals fall to the ground. But you should not despair because it fertilises the ground for the next flower'. [SUNDAY TIMES, SINGAPORE]

|

Return to Singapore DharmaNet